Background

The state of Rhode Island is implementing sweeping changes for high school graduation requirements that leaders anticipate will open avenues of opportunity for thousands of students each year, creating college and career ready high school graduates equipped with real-world skills that are ready to take on the rigors of academia and transition into high-demand professions.

Rhode Island Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Angélica Infante-Green said she’d been leading the state’s schools for a little over a year. That’s when she first came face-to-face with the reality that Rhode Island wasn’t preparing students for their futures, shortchanging not only the students, but potentially crippling the state’s future workforce. That was 2019, when Infante-Green participated in school planning sessions with educators and students to deeply explore what the high school experience was like for students.

“As the person leading Rhode Island’s state education system, I was devastated to hear students and teachers describing a system that frankly wasn’t preparing kids for success in college or careers. We needed to figure out whether this was happening at a few high schools or whether it was a more widespread problem.”

Angélica Infante-Green

A deeper audit in 2020 revealed just how prevalent and pervasive the challenges were. After analyzing thousands of transcripts and surveying students and parents, Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) leaders learned that what students wanted and what their high schools provided them didn’t line up. Even more alarming, schools were failing to help students meet basic requirements that would allow them to enroll in colleges and universities and prepare them to thrive.

“Until recently, we’ve had one of the lowest-rigor high school diplomas in the country,” said Steve Osborn, State Strategy and Student Opportunity Officer at RIDE. “And there were just huge equity gaps across the state.”

For example, through surveys and transcript analysis of a representative sample of students across the state, RIDE learned that while 80 percent of Rhode Island high schoolers said they wanted to go to college, only 60 percent were taking the classes necessary to get them there. And, even more concerning, of those taking the courses needed to prepare them for college, only about half were passing them.

The statistics were even worse for low-income students, students with limited English proficiency, and students with disabilities. For low-income students and English learners, only 42 percent who took classes needed for college passed those classes, and for students with disabilities, just 12 percent.

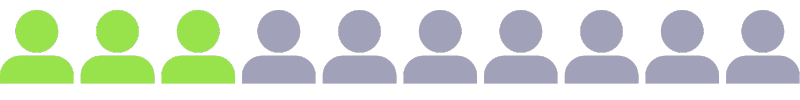

Rhode Island High Schoolers

80% of high schoolers say they want to attend college.

60% of high schoolers were taking courses necessary for college admission.

30% of high schoolers were passing courses necessary for college admission.

When that alarming information was presented to the Rhode Island Council on Elementary and Secondary Education and the state’s education commissioner, they gave an immediate green light to create a new division in the state’s education department with the sole focus of reimagining the high school experience. To achieve this, Rhode Island education leaders recognized they needed data beyond test scores and graduation rates. Policy makers needed to understand what aspirations students hold for themselves, what barriers keep them from reaching those aspirations, what motivates and inspires them, and what skills they need to be successful in college or in the job market.

The Solution

The enormity of tackling the challenge of school reform – particularly at a statewide level – generally means it’s done in phases – addressing one problem at a time. But Rhode Island’s state education leaders wanted sweeping changes, and they wanted them fast.

According to Osborn, who was tapped to lead the new initiative, Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green had a simple but powerful message: “We go big.”

“When you give clear, compelling data to driven people, there is a call to action,” Osborn said. “We are blessed in Rhode Island to have a great commissioner and a great board chair who wanted to get things done for our kids.”

Getting things done, Rhode Island style, meant a total revamp of the state’s graduation requirements; ambitious community engagement that sought input from every high school student, parent, teacher and administrator in the state; as well as robust conversations with local communities, job creators, colleges and universities. Eighteen months after the initial audit findings, Osborn and his team were presenting the most commented on education policy revision and the single most impactful changes to graduation requirements in the state’s history.

To accomplish this ambitious goal, RIDE partnered with Abl for in-depth analysis that went beyond the 2020 audit. Abl’s team of veteran educators and data researchers analyzed individual student transcript data statewide.

The team mapped out each student’s academic journey, identifying startling inequities and faulty scheduling practices that, in some cases, set a course for students as young as ninth grade that would make it difficult, if not impossible, to move on to college.The transcript analysis found that problems start early: By the end of freshman year, 14 percent of students are off track for college eligibility. And of those, nine out of 10 would never catch up.

The state-wide estimate of college eligibility and readiness ultimately was used to understand K-12 preparation and develop targeted policy. In addition to the quantitative state-wide analysis of post-secondary readiness using Abl’s evidence-based Educational Opportunity Assessment, the team helped Osborn and his colleagues collect qualitative survey data from parents, teachers, and students. Abl also helped host dozens of focus groups to understand perceptions of how well schools were preparing students for their futures.

“It led to some of the most raw conversations we’ve ever had. The process was powerful,” Osborn said. “You can’t dismiss a group of kids right in front of you. We had multiple school teams literally in tears when they realized how poorly they were preparing kids for what they wanted to do.”

It led to some of the most raw conversations we’ve ever had. The process was powerful. You can’t dismiss a group of kids right in front of you. We had multiple school teams literally in tears when they realized how poorly they were preparing kids for what they wanted to do.

Stephen Osborn

Abl’s Methodology

Abl’s methodology relies on collecting complete course-taking histories for the most recently graduated cohort of students, including course titles, grades, and test scores. Abl then conducts a thorough review of all courses, codes them, and applies meta-coding to allow for trend and pattern analysis in the course-taking data. Each student is assigned an Academic Intensity Measure (AIM) score that is based on a composite of the following areas of analysis:

Persistence

An analysis of how many years of postsecondary preparatory coursework students complete in English, math, science, social studies, and world languages.

Advanced Coursework

An analysis of the number and subjects in which students complete advanced course work such as honors, dual credit, college in the high school, and Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate coursework.

Course Progression

An analysis of the highest level of math coursework that is completed and specific science sequences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics) that are highly indicative of post-secondary momentum.

In each of these measures, specific attention is given to historically underserved student groups. The aggregate results of this analysis provide school districts with a comprehensive understanding of the overall body of coursework by students, disparities in student outcomes, how students navigate through course offerings, what guidance and advising systems are in place, and overall student readiness for college and career.

Some of the problems included scheduling conflicts where important support classes needed by students with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) were only available when classes required for college admission were also scheduled. This forced students and parents to choose between their IEP support and the classes that would prepare them for college. To remedy this, one of the new state policies mandates that scheduling cannot be a barrier to a student’s opportunity. Schools must find a way for students to take both IEP support classes and courses needed for college entrance – such as advanced math or foreign language.

During focus groups, many students also shared stories about not knowing what classes they needed to take to be college ready until it was too late, which is why the state shifted its new graduation requirements to line up with college admission requirements. Osborn said this also highlighted the need for better school counseling and prompted a five-year action plan which includes a refocus on counseling in high schools.

“You can’t help connect kids to goals and their future unless you have an adult in the school building whose job it is to guide and advise them on that journey,” he said.

Abl’s Director of College and Career Readiness Steven Gering said mapping individual student journeys through high school and collecting data to understand what goals and aspirations students had for themselves revealed alarming gaps.

“We found massive disparities in terms of course taking,” Gering said. “There were clear equity issues. We were there to help facilitate those school conversations and face that data head on.”

Some of Abl’s findings included:

- Roughly six out of 10 students in Rhode Island were taking the courses they needed to be eligible for college. Boys were less likely to complete the college preparatory course sequence than girls, while Black and Latino students were less likely than white and Asian students, and low-income students and English learners were less likely than their peers. Students with disabilities had the lowest rate of all.

- Only about a third of students were taking the full complement of career and technical education courses needed to be considered career-ready.

- Just over half of students – 52% – graduated eligible for college. Outcomes were significantly worse for underrepresented demographic subgroups, including low-income, English language learners, and students with disabilities.

The Results

This data was shared statewide with superintendents, principals, parents, teachers, students and community leaders. RIDE and Abl criss-crossed the state, meeting on a bi-weekly basis with the state’s superintendents’ association, holding focus groups at high schools and with community organizations. Osborn said sometimes they set up shop at a local library or rec center to connect with as many Rhode Islanders as possible.

After gathering historic levels of community input, writing, revising, and writing again to address all concerns, Osborn and team presented new graduation standards to the State Council on Elementary and Secondary Education in November 2022. They were approved unanimously and take effect for this year’s eighth-graders.

The new standards include at least two years of the same foreign language, and completing both Algebra II and Geometry – all required for admission to the University of Rhode Island, Rhode Island College, and most four-year institutions across the nation.

But the standards go far beyond providing a clear path to college. By leveraging a process that included wide-ranging conversations and asking communities what Rhode Island high school graduates should know and be able to do, state education leaders addressed myriad concerns and inequities in the previous system.

Beginning with the Class of 2028, seniors will graduate having written professional resumes and with support to complete the federal college financial aid form, known as FAFSA. Students will also take classes in financial literacy, civics, and computer science – a request state leaders heard time and again in focus groups and community meetings.

“It is kind of staggering when you consider 17-year-olds are asked to take out six-figure loans and they have no idea what that means. Students told us they want to learn how to manage money and they want to learn more about how to get engaged in their communities. If you think about it, you can’t have well rounded people graduating high school without knowing how to manage money and how to engage in their community.”

Stephen Osborn

The new requirements also eliminate seat time in the classroom – a longstanding criteria for earning academic credit – in an effort to address systemic inequities. Hearing stories from students who were working to help support their families or acting as caregiver for a sibling, parent or grandparent and not always able to attend class or arrive on time were hugely impactful for policy makers.

“One of the goals of this process was to reimagine what the student experience looked like. That process introduced us to a whole other world of students, students that are working to support their families, lifting their families out of poverty,” Osborn said. “They’ve been unseen, unheard and undefined until now.”

Instead of “seat time,” the new regulations focus on mastery. They also enable students to earn credit for caregiving, and other real-world experiences, and allow schools to combine courses for “flex credits.” For example, algebra could be taught in the same class with physics or English with theater.

Schools aren’t on their own to implement these changes. Abl produced a customized, 100-page report for each school and provided support to each campus to develop an action plan. Osborn has also created a Community of Practice across the state to provide ongoing collaboration and guidance for high schools across the state.

Osborn said the entire process has been more powerful than he could have imagined. And heading into conversations with an open mind was key.

“The goal wasn’t to be right, but to get it right for our kids,” Osborn said. “If you look at all the changes, all the progress we’ve made, the Abl work is the underpinning of everything we’ve been able to accomplish.”

There is room for exceptions in the new requirements. State education leaders recognize that not everyone is college bound and did not want to create a barrier for some students to earn a diploma. With informed consent of a parent or guardian, students can register for a readiness pathway that may not include requirements such as higher level math or foreign language. But the key difference is only the parent and student can make that decision – not the school.

“What Abl provided was the vehicle to have this conversation,” Osborn said. “The Educational Opportunity Analysis helped us go under the hood, and push school teams from all backgrounds to do better, both low and high performing.”

Commissioner Infante-Green emphasized that seeking input and truly listening was critical to driving progress. For far too long, public education has been a top-down effort with little to no attention focused on those who are at the heart of the issue.

“What policymakers often forget is that when a major change is proposed, people get nervous. There were many moments along the way when, if we’d failed to engage our school system’s diverse stakeholders, we would have lost crucial support,” Infante-Green said. “But RIDE committed to shepherding our communities through this process, remaining flexible, addressing their concerns and devising solutions, and we kept that commitment. That’s the main reason this effort succeeded: We did not want to be right, we wanted to get it right with the community by our side.”

Download Case Study

“We aspire to an educational system that holds high expectations for all students, regardless of income or background; is responsive to students’ individual needs; and pushes the boundaries of imagination and innovation to create better learning conditions for students and educators.”

– Rhode Island Strategic Plan for Education