Breaking Down Barriers

A Multiphase Approach to Transforming Your Scheduling Practices and Unlocking Lifelong Opportunity for Students

Steven Gering, EdD and Wendy Watson, EdD

Introduction

Technical Problems vs. Adaptive Challenges

In the article “A Survival Guide for Leaders,” Cambridge Leadership Associates co-founders Ron Heifeitz and Marty Linsky discussed the importance — and difficulty — of leaders distinguishing between technical problems and adaptive challenges (see Table #1). To help illustrate their point, they used the analogy of a car.

“When a car has problems, you go to a mechanic. Most of the time, the mechanic can fix the car. But if your car troubles stem from the way a family member drives, the problems are likely to recur. Treating the problems as purely technical ones—taking the car to the mechanic time and again to get it back on the road—makes the real issues.”1Heifetz, Ronald & Marty Linksy. “A Survival Guide for Leaders.” Harvard Business Review, 2002, Cambridge, MA.

Many district and high school leaders treat school scheduling the same way. They see the schedule as a technical problem that they need to solve each spring. The goals are typically to ensure that all students receive the courses necessary to earn a high school diploma, staff members are assigned to courses, students receive schedules, and each course has a room. And because leaders see scheduling as a technical problem, they often delegate it to staff members who have strong technical expertise to complete the process but who often are not responsible for implementing strategic district goals and initiatives.

This traditional approach to scheduling assumes that scheduling is primarily technical in nature — when, in fact, it is an adaptive leadership challenge. Preparing students for the new realities of the current economic environment requires a mindset shift, new perspectives, perceptions, and orientation to the work to prepare all students for college and career opportunities.

Table #1: Technical Problems vs. Adaptive Challenges2NCS Postsecondary Success Toolkit: Toolset B. “Technical Problems vs. Adaptive Challenges.” Network for College Success, The To & Through Project, and the University of Chicago School of Social Services and Administration, 2017, Chicago, IL.

In the context of leadership and management, this table provides a comparison of technical problems, which have clear solutions and known procedures versus adaptive challenges, which are complex, demand learning and adaptation, and often require changes in deeply held beliefs and behaviors.

TECHNICAL PROBLEMS

A technical problem is an issue with a clear and known solution that can be addressed using existing knowledge, expertise, and established procedures.

Clear Solutions: Technical problems are issues that can be resolved using existing knowledge, expertise, and established procedures. They have clear and known solutions.

Known Procedures: Solutions to technical problems often involve applying standard operating procedures, best practices, or well-defined methods.

Expertise: Usually, technical problems can be tackled by experts or specialists who possess the necessary skills and knowledge.

Routine Fixes: The solutions to technical problems are typically not disruptive and do not require significant changes to the current system or way of doing things.

Single Authority: Technical problems can often be addressed by a single authority or a group of experts.

ADAPTIVE PROBLEMS

An adaptive challenge is a complex problem that lacks a clear solution and requires individuals and organizations to learn, adapt, and possibly change their deeply held beliefs and behaviors to address it effectively.

Complex and Unpredictable: Adaptive challenges are complex, multifaceted problems that lack clear, predefined solutions. They often arise in dynamic and changing environments.

Requires Learning: Solving adaptive challenges usually requires individuals and organizations to learn and adapt, possibly changing their deeply held beliefs, values, and behaviors.

Leadership Required: Addressing adaptive challenges often necessitates strong leadership that can mobilize people to confront the issue and engage in the difficult process of adaptation.

No Quick Fixes: There are no quick fixes or ready-made answers for adaptive challenges. They require experimentation, innovation, and the ability to deal with ambiguity.

Conflict and Resistance: Tackling adaptive challenges may lead to conflict and resistance because it involves challenging the status quo and making difficult choices.

National Context: The Economy and Educational Attainment

Economic forecasts prior to the COVID-19 pandemic predicted that 7 out of 10 jobs would require some form of postsecondary education by 2030.3Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce forecast using data from the US Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey; US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Macroeconomic Advisers LLC; and EMSI (formerly Economic Modeling Specialists International). While it is still too early to precisely predict what will happen in the short-term U.S. economy, evidence suggests that the combination of technology4 Hershbein, Brad, and Lisa B. Kahn. “Do Recessions Accelerate Routine-Biased Technological Change? Evidence from Vacancy Postings.” American Economic Review vol. 108, no. 7, 2018, pp. 1737–72; Carnevale, Anthony P., Tamara Jayasundera, and Artem Gulish. America’s Divided Recovery: College Haves and Have-Nots. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2016, Washington, DC. and economic forces5Carnevale, Anthony P., Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl. “Help Wanted: Projections of Jobs and Education Requirements through 2018.” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2010, Washington, DC. will favor upskilling in the U.S. workforce.6Carnevale, Anthony P, Jeff Strohl, Nicole Smith, Ban Cheah, Artem Gulish, and Kathryn Peltie. “Navigating the College to Career Pathway: The 10 Rules of Moving from Youth Dependency to Adult Economic Dependence.” Georgetown Center for Education and the Workforce, 2019, Washington, DC.

Overall, most of the evidence indicates that the fastest-growing occupations will require postsecondary education, and even midskilled occupations that traditionally have required lower levels of education to enter the workforce will require continued upskilling.

Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in enrollment and degree attainment rates in postsecondary education. However, there are clear disparities in who is achieving success. These disparities become even more significant when examining who persists and graduates from college. Among adults ages 25 and older, only 28% of the Black population and 21% of the Hispanic population have attained a bachelor’s degree compared to 42% of the White population and 61% of Asian Americans. These disparities, coupled with the increased demand for employees with postsecondary education, highlight the need for action to ensure that students have access to the opportunities and resources they need to graduate ready for college and career opportunities.7Schaeffer, Katherine. “10 Facts About Today’s College Graduates.” Pew Research Center, 2022, retrieved 9/27/23 from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/04/12/10-facts-about-todays-college-graduates/.

Research: Academic Intensity and Student Outcome Gaps

Given the increasing demand for postsecondary education, it is crucial for K-12 education to adequately equip students to succeed in their postsecondary pursuits. The intensity of the coursework that students complete in their secondary school experience and their performance in those courses are some of the most important and predictive metrics that leaders can influence to alter student college and career readiness (CCR) trajectories.8Wiley, Andrew, Jeffrey Wyatt, and Wayne J. Camera. “The Development of a Multidimensional College Readiness Index.” College Board, 2011, New York, NY. 9Barnett, Elisabeth. “Building Student Momentum from High School into College.” Community College Research Center and Jobs for the Future, 2016, Boston, MA. 10Long, Mark C., Dylan Conger, and Patrice Iatarola. “Effects of High School Course-Taking on Secondary and Postsecondary Success.” American Educational Research Journal, v 49 n2 p 285-322, April 2012.

However, national trends outlined by the U.S. Department of Education illustrate that districts across the nation are challenged to provide intense learning experiences with consistent outcomes for their students. Furthermore, the courses and programs that are most correlated with postsecondary success are underenrolling students of color, students from rural areas, and students living in poverty.

Figure #1: Black and Latino Access to Gifted and Talented, Advanced Placement (AP), and Advanced Mathematics Courses11U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. “Civil Rights Data Collection Data Snapshot: College and Career Readiness.” CRDC, 2014, Washington, DC.

To address these disparities and ensure that each student is prepared for success in the world, school districts must examine their systems and policies to ensure that each student has the opportunity to design an academic journey that accounts for their unique background, strengths, and passions. Simultaneously, districts need a comprehensive approach to help students and families navigate the complex pathways to successfully obtain credentials and degrees in postsecondary education.

Why Strategic Scheduling

Schools and districts don’t operate with large discretionary budgets. Approximately 80% of the total operating budget is invested in people.12National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Public School Expenditures. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved 5/14/23, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cmb. However, school and district leaders spend a majority of their time strategizing how to spend the other 20% that is discretionary. Far less attention is given to the 80% of the budget that is allocated to the courses taught, the staff members assigned to those courses, and how students are enrolling and completing coursework.

An inequitable school schedule can have significant consequences for students, limiting their access to advanced coursework and preventing them from receiving the personalized instruction they need. However, designing core systems with equity at the center can assist students by removing barriers and transforming their educational experiences and academic outcomes.

Abl places a particular focus on strategic scheduling (see Table #2), recognizing its cascading impact on other systems within a school and district. The schedule determines how a school allocates resources, including time, personnel, and physical spaces. The schedule shapes fundamental aspects of the student experience such as their interactions with teachers and peers, class size and composition, access to additional supports and services, and opportunities to take courses and electives aligned with their interests and postsecondary goals. Operational decisions also impact teachers’ course loads and whether they have scheduled time for collaboration, planning, and professional development to deliver high-quality instruction.

These formative decisions are made by a range of school leaders — including guidance counselors, assistant principals, principals, and superintendents — well before students ever set foot in the classroom. Because every school in the United States has a schedule, developing and promoting strategic scheduling principles is critical to ensuring that students remain at the center of our education system.

Table #2: Traditional Scheduling vs. Strategic Scheduling

An outline of the differences between two different scheduling approaches: traditional scheduling where work is often viewed as a technical problem that needs to be solved each spring compared to strategic scheduling where the work is seen as an adaptive challenge at the center of district and school improvement efforts.

Traditional Scheduling (Technical)

VIEW

Scheduling is an isolated task to be completed in the spring.

GOAL

Scheduling prepares students for high school graduation.

OUTCOMES

Students have complete schedules with a focus on managing behaviors across the school.

DRIVING FORCE

Schedules are driven by adult needs and priorities.

CREATORS

School schedules are created by data clerks or counseling teams with little school leadership oversight.

HALLMARKS

- Course requests are conducted in large group formats with minimal one-on-one advisement.

- Information for students and families is available passively for those who seek it.

- Student course requests are fulfilled with no active intervention when significant student outcome disparities are evident.

- Administrative course prerequisites create enrollment barriers for students.

VIEW

Scheduling is an isolated task to be completed in the spring.

GOAL

Scheduling prepares students for high school graduation.

OUTCOMES

Students have complete schedules with a focus on managing behaviors across the school.

DRIVING FORCE

Schedules are driven by adult needs and priorities.

CREATORS

School schedules are created by data clerks or counseling teams with little school leadership oversight.

HALLMARKS

- Course requests are conducted in large group formats with minimal one-on-one advisement.

- Information for students and families is available passively for those who seek it.

- Student course requests are fulfilled with no active intervention when significant student outcome disparities are evident.

- Administrative course prerequisites create enrollment barriers for students.

Strategic Scheduling (Adaptive)

VIEW

Scheduling is a key, year-round process that is at the center of the school improvement cycle.

GOAL

Scheduling prepares students for success in college and career.

OUTCOMES

Students have intense schedules that reflect their individual goals and postsecondary aspirations.

DRIVING FORCE

Schedules are driven by predictive analytics and a student’s postsecondary interests.

CREATORS

School schedules are developed by school leaders and involve multiple stakeholders in the building and district.

HALLMARKS

- Students receive extended one-on-one or small-group advisement to assist them in selecting their courses.

- Time is allocated to ensure that all students have access to the same information to help guide their course requests.

- Recruitment for intense courses is targeted and prioritized for all students.

- Key CCR metrics are monitored on an annual basis and leaders actively intervene to ensure all students are prepared for college and career.

VIEW

Scheduling is a key, year-round process that is at the center of the school improvement cycle.

GOAL

Scheduling prepares students for success in college and career.

OUTCOMES

Students have intense schedules that reflect their individual goals and postsecondary aspirations.

DRIVING FORCE

Schedules are driven by predictive analytics and a student’s postsecondary interests.

CREATORS

School schedules are developed by school leaders and involve multiple stakeholders in the building and district.

HALLMARKS

- Students receive extended one-on-one or small-group advisement to assist them in selecting their courses.

- Time is allocated to ensure that all students have access to the same information to help guide their course requests.

- Recruitment for intense courses is targeted and prioritized for all students.

- Key CCR metrics are monitored on an annual basis and leaders actively intervene to ensure all students are prepared for college and career.

Ultimately, strategic scheduling is different because it requires leaders to approach the work with an adaptive mindset. Leaders are not simply completing a task; instead, they use metrics and goals to guide their decision-making. This approach requires active intervention and leadership over the course of the entire year to ensure that all students have access to the necessary coursework and resources to meet their postsecondary goals and become engaged members of their communities.

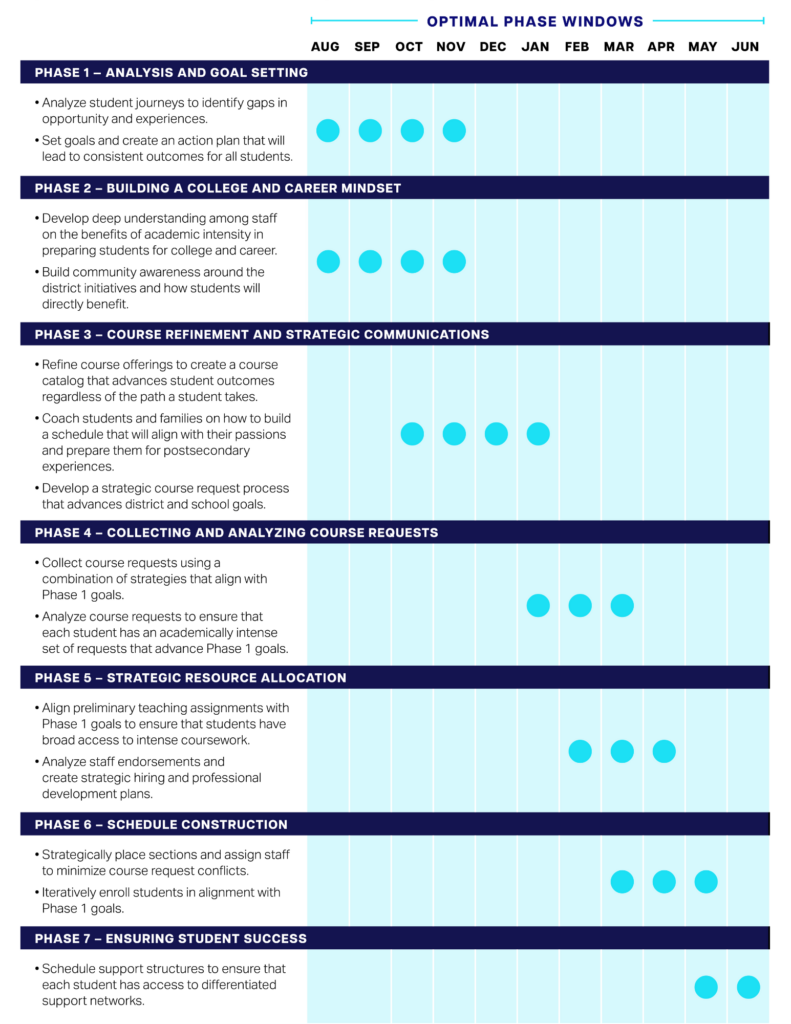

Abl’s Seven Phases of Strategic Scheduling

Moving the school schedule from a technical task each spring to an adaptive and strategic process requires new thinking, cultural change, stakeholder engagement, robust conversations, and transformative leadership and learning. To assist in that transformation, Abl has developed a comprehensive approach (see Figure #2) that centers strategic scheduling as one of the major cornerstones of secondary school and district leadership. In this framework, strategic scheduling is a multiphased, year-round, adaptive leadership process that ensures all students have viable options that will prepare them for success in college and career.

Figure #2: Abl’s Seven Phases of Strategic Scheduling

Phase 1 – Analysis and Goal Setting (August – November)

- Analyze student journeys to identify gaps in opportunity and experiences.

- Set goals and create an action plan that will lead to consistent outcomes for all students.

Phase 2 – Building a College and Career Mindset (August – November)

- Develop deep understanding among staff on the benefits of academic intensity in preparing students for college and career.

- Build community awareness around the district initiatives and how students will directly benefit.

Phase 3 – Course Refinement and Strategic Communications (October – January)

- Refine course offerings to create a course catalog that advances student outcomes regardless of the path a student takes.

- Coach students and families on how to build a schedule that will align with their passions and prepare them for postsecondary experiences.

- Develop a strategic course request process that advances district and school goals.

Phase 4 – Collecting and Analyzing Course Requests (January – March)

- Collect course requests using a combination of strategies that align with Phase 1 goals.

- Analyze course requests to ensure that each student has an academically intense set of requests that advance Phase 1 goals.

Phase 5 – Strategic Resource Allocation (February – April)

- Align preliminary teaching assignments with Phase 1 goals to ensure that students have broad access to intense coursework.

- Analyze staff endorsements and create strategic hiring and professional development plans.

Phase 6 – Schedule Construction (March – May)

- Strategically place sections and assign staff to minimize course request conflicts.

- Iteratively enroll students in alignment with Phase 1 goals.

Phase 7 – Ensuring Student Success (May – June)

- Schedule support structures to ensure that each student has access to differentiated support networks.

Up Next

Phase 1: Analysis and Goal Setting

It is unlikely school leaders will make progress on their CCR goals if they are not annually using data to set goals, track progress, actively reflect on student outcomes, and adjust implementation efforts along the way. Adaptive leadership in this phase involves clearly identifying trends and challenges in the data and actively problem-solving to improve CCR for all students.