Breaking Down Barriers

A Multiphase Approach to Transforming Your Scheduling Practices and Unlocking Lifelong Opportunity for Students

Steven Gering, EdD and Wendy Watson, EdD

Phase 3: Course Refinement and Strategic Communications

“We find substantial significant differences in outcomes for those who take rigorous courses and those estimated effects are often larger for disadvantaged youth and students attending disadvantaged schools.”1Long, Mark C., Dylan Conger, and Patrice Iatarola. “Effects of High School Course-Taking on Secondary and Postsecondary Success.” American Educational Research Journal Vol. 49, No. 2 April 2012, Washington D.C.

Course Refinement

When schools and districts provide students with personalized and robust course-taking advice and ensure there is a strong CCR culture and environment of academic press, they are then prepared to consider numerous strategies to refine course offerings. Refining course offerings is an opportunity to accomplish the following:

- Narrow course offerings to focus on fewer courses of higher quality and intensity.

- Remove barriers that prevent students from accessing intense coursework.

- Add courses to enhance student CCR.

NARROW COURSE OFFERINGS

In the 1980s, Ted Sizer wrote a book called “Horace’s Compromise,” and it spawned other books such as “The Shopping Mall High School.”2Powell, Arthur G., Eleanor Farrar, David K. Cohen, National Association of Secondary School Principals, National Association of Independent Schools Commission on Education. “The Shopping Mall High School: Winners and Losers in the Educational Marketplace.” Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1985. 3Sizer, Theodore R. “Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School.” Harper Paperbacks, 1984. In these books, the authors lamented about the idea that bigger is always better and that more course offerings are not necessarily synonymous with quality. Secondary schools often try to replicate course offerings from colleges and this can result in large variation in course quality, leading to inequities in student experiences and college and career outcomes. It is often adventageous for districts and schools to remove a number of courses from the course offerings that are not advancing CCR goals.

Remove Course Offerings

Although it is counter to beliefs about more being better, students typically benefit from a reduction of course offerings. This has the potential to improve efficiency, increase advanced course enrollments, provide teachers opportunities to collaborate, create opportunities for focused professional development, and can ultimately lead to reduced levels of tracking. Another added benefit of reduced course offerings is a corresponding reduction in necessary advice and guidance for students and families. Abl works with districts and schools across the country that are hesitant to reduce their course offerings and ask whether more is necessarily a bad thing.

The advice Abl provides is that more offerings are not a bad thing by themselves; however, a large volume of offerings almost always requires more counseling, guidance, and advice to provide students and families with the necessary background information to navigate the volume of choices and pathways being presented.

Eliminate Excessive Tiers of Coursework

Another key strategy is to remove core classes from the schedule that create tiers of coursework, to meet one graduation requirement. For example, if the majority of sophomores typically take chemistry, schools should offer one chemistry class and one advanced chemistry class. Both classes should have a CCR focus with an opportunity for many to challenge themselves with a college-level chemistry class. Avoid offering a third chemistry class designed to lower standards to help students who struggle with the content. When school leaders allow tiered courses to meet one graduation requirement, they inadvertently eliminate a CCR-for-all mindset. Multiple tiers of coursework also allow for staff bias to consciously or subconsciously place historically underserved students in low-end coursework.

Remove/Revise Non-Postsecondary Aligned Electives

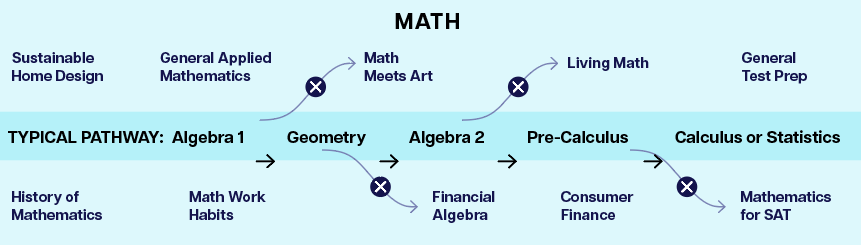

Remove distracting electives from the curriculum that are not aligned with overall CCR goals. Schools are likely offering several courses that are not adequately preparing students for postsecondary pursuits. This can include electives such as the following: Teacher Assistant, Late Arrival, Early Release, as well as elective courses within all subject areas (see Figure #4)

Figure #4: Narrow Courses Distracting Students from Desired Course Progression

Example of math course offerings at a large comprehensive high school and how the elimination of non-postsecondary aligned elective courses can improve CCR outcomes for all students.

Evaluate and Align Cross-Credited Coursework

Another frequently overlooked aspect of narrowing, is the need to continually evaluate and align cross-credited coursework. In the past several years, there has been a proliferation of courses that meet multiple graduation requirements. While this can be a useful strategy and great opportunity for students, it is critical for district leaders to evaluate whether these courses are authentically covering curriculum standards from two different disciplines and whether they are preparing students for postsecondary options. While many courses meet these requirements, some do not have the necessary content standards and rigor to warrant the cross-credited designation. For example, a CTE course such as Sewing Construction and Design may be approved for CTE credit as well as science credit (for chemistry) and mathematics credit (geometry). Using this example, it is important to look at the actual standards and course content that are being taught in the cross-credited course and ask, “Are students actually learning the equivalent course content for a full science or mathematics course?” These are typically extremely difficult conversations to have because they require either removing cross-credited status for a particular course or substantially changing the course content and curriculum of the cross-credited course to fully align.

Myth vs. Reality

MYTH:Student course intensity does not matter as long as they graduate.

REALITY: Recent data from a national transcript study indicates that high school graduates are earning more credits, especially in academic subjects; GPAs are rising; and students are completing more STEM courses than ever. While this seems like good news, the study also indicates that National Assessment of Educational Progress math scores have dropped during the last decade, and science scores have remained flat. “What we found is that the titles and what was being advertised by the schools as an advanced course in these areas really did not pan out when we actually looked at what was being taught,” said National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Commissioner Peggy Carr.4

Sparks, Sarah D. “12th Graders Took Harder Courses and Got Higher GPAs,, but Test Scores Fell. What Gives?” Education Week, 2022, retrieved 9/27/23 from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/12th-graders-took-harder-courses-and-got-higher-gpas-but-test-scores-fell-what-gives/2022/03.

The research is clear. Curriculum matters, and students who complete intense coursework are more likely to pursue and succeed in their postsecondary coursework and career pursuits. Creating new course titles indicating students are enrolled in intense coursework does not provide them with access to rigorous curriculum and will not replicate the study’s results.

Previous studies by NCES analysts concluded that only 18% of Honors Algebra I courses and 33% of Honors Geometry courses used a rigorous curriculum. It is imperative that school leaders pay attention to the content and standards of each course offered and delivered to students. They deserve access to high-quality curriculum and not new titles that are devoid of rich content to prepare them for a variety of postsecondary pursuits.

REMOVING BARRIERS

One challenge with strategic scheduling can occur when courses are present in the course catalog but few students access and enroll in the courses. Two common culprits of low student enrollment in intense coursework are formal and informal barriers that make it difficult for students to successfully request and enroll in targeted courses.

Formal Barriers

Formal barriers are structures that schools put in place where students must meet a requirement or set of requirements to gain approval to sign up for a course. Examples of formal barriers can include the following:

- Teacher recommendations.

- Teacher signatures.

- Minimum GPA.

- Completion of specific coursework.

- Specific grade-level requirements (as opposed to student competency).

At times, some formal barriers to enrollment make sense. For example, it is logical for students to complete Algebra I before enrolling in Algebra II. But many times, formal barriers to enrollment are not necessary and are even arbitrary. Does evidence support that students need a 3.6 GPA to enroll in AP Language and Composition to be successful? Some formal barriers may appear easy for students to obtain or overcome (e.g., teacher signature), but not all students have the same social capital that makes them comfortable asking a teacher they do not know for a signature to enroll in a course. It is imperative that school and district leaders examine any formal barriers that are in place and evaluate whether they need to remain in place. It may take time and effort to successfully get staff buy-in and support to remove these formal barriers, but it can result in increased access.

Informal Barriers

After removing formal barriers, school leaders should also address informal barriers that prevent students from enrolling. Examples of informal barriers can include the following:

- A student’s self-perception of abilities.

- Lack of belongingness due to cultural or socioeconomic status.

- Tradition or historical practices (e.g., historically only juniors enrolling in AP Language and Composition when it could be a great option for senior students as well).

- Lack of social capital to navigate CCR expectations and habits.

For example, it is possible to remove formal barriers to access AP English 11 in the course registration materials. But when examining enrollment trends and data, it may be apparent that 100% of enrollment is coming from English 10 Honors. If students are not signing up for a course, informal barriers or perceptions may be preventing students from considering whether they are qualified for the course. It is important to analyze enrollment patterns on a regular basis to ascertain whether informal barriers exist. In those cases, it may take leaders actively recruiting and involving students to have large breakthroughs in enrollment patterns.

ADDING COURSES TO THE COURSE CATALOG

The data analysis from Phase 1 of strategic scheduling may reveal areas of limited or few advanced course offerings. In those cases, leaders should thoughtfully and strategically add new courses into the catalog to increase student CCR.

Dual-Credit Opportunities

One research backed method is to provide all students access to dual-credit coursework while they are enrolled in high school. Common programs to increase enrollment in dual-credit coursework include:

- AP, IB, and Advanced International Certificate of Education.

- College in high school.

- Dual-enrollment programs.

While each program has different pros and cons associated with implementation, cost, and outcomes, they all offer students the opportunity to experience rigorous coursework while enrolled in high school. Additionally, they all provide students the opportunity to earn college credits and reduce the time necessary for post-secondary degree completion.

Support Courses

Another strategy for refining course offerings includes adding courses to the schedule that offer support for students to master content in intense courses. For example, schools can provide one period a day for students to work with a teacher to master course content and objectives.

Additional Years of Coursework

Not all additions to course offerings must be dual-credit or support courses. Schools may find significant benefit from offering additional years of coursework to enable students to continue past minimum course requirements. These courses can occur in any subject area but are commonly accessed in world languages, science, and mathematics. For example, adding a third or fourth year of a world language progression, which may or may not include dual-credit opportunities, increases overall student academic intensity.

In STEM subjects, there are still low percentages of students completing the following:5

National Center for Education Statistics. “High School Mathematics and Science Course Completion.” Institute of Education Sciences, May 2022, Washington DC.

- Biology, Chemistry, and Physics (35% of students complete).

- Physics (40% of students complete).

- Calculus (16% of students complete).

- Precalculus/Mathematical Analysis (40% of students complete).

- Probability and Statistics (17% of students complete).

As an example, physics is a key gatekeeper and cornerstone of many professions, including those in engineering, health care, aerospace, and architecture. For STEM majors, having access to physics can provide a significant leg up in accessing these majors and succeeding in introductory postsecondary coursework.

Yet, as recently as 2016, 2 in 5 high schools didn’t offer physics. And researchers found in their analysis tremendous variation across states. For example, “In both Alaska and Oklahoma, about 70 percent of high schools don’t offer the course. Florida and Utah are close behind, with nearly 60 percent of high schools lacking physics.”6Loewus, Liana. “2 in 5 High Schools Don’t Offer Physics, Analysis Finds” Education Week, 2016, Bethesda, MD.

KEY ACTIONS

These are just some examples of ways to improve student academic intensity via world languages and STEM, and these are not meant to be exhaustive. The key idea is that academic intensity does not necessarily mean that students have to complete advanced coursework. At times, having students continue to complete coursework above and beyond minimum graduation requirements can significantly increase overall academic intensity and CCR.

It is critical for schools to ensure that all students have access to high-quality, intense courses that prepares them for a variety of postsecondary pursuits. It is important for school leaders to do the following:

- Thoughtfully vet all course offerings.

- Remove courses that do not align with postsecondary goals and outcomes.

- Eliminate barriers that prevent students from accessing accelerated coursework.

- Add in rigorous course offerings to provide all students access to an intense and CCR preparatory curriculum.

Myth vs. Reality

MYTH: Every district approved course needs to be offered at every school.

REALITY: In most school districts, the school board approves which courses are taught and the curriculum associated with these courses. At times, specific courses are required to meet district graduation requirements. This is all in the district’s purview.

However, just because the district approves a course does not mean that each school must offer the course. School leaders can eliminate courses that do not align with school goals.

Strategic Communications

COURSE OFFERINGS AND ACADEMIC ADVISING

Once schools have refined courses, the next step involves creating materials to guide students and families through the course offerings and designing advising structures to support students in learning about their options.

The course request process begins months before students put their information on a course request form. In an ideal guidance setting, all staff members are actively engaged as advisors, and families receive personalized attention to make informed choices. Staff members need actionable tools to have these conversations and recruit students into intense coursework, and reports to support a focus on students typically underrepresented at the college level. For example, advisors should have lists of their students who would benefit from being recruited into advanced coursework prior to the actual course request process being completed so they can use that information in their conversations with students and their families.

Another assumption is that within a pre-registration advisory setting, students have previously taken surveys linked to college and career interest surveys, and advisors have had time to analyze the results to help students choose courses based on a multi-year plan connected to their postsecondary aspirations. Schools that build a college-going culture invest resources in one of many online programs that provide survey options connected to college and career information.

Table #7: Key Information as Part of a Comprehensive Communication and Advising Campaign

The goal of the communication campaign is to level the playing field so all families are operating from similar starting points as they make these important decisions. If families are making decisions based on outside information or knowledge, then it can result in large inequities in student course requests and enrollment patterns.

The Why of CCR

Actively communicate to students and families the importance of accessing and completing intense coursework in preparation for postsecondary opportunities.

Logistics of Postsecondary Eligibility and Access

It is important to address graduation requirements and admission standards for colleges. Schools should include information for juniors and seniors outlining college readiness timelines: researching colleges, exploring apprenticeship opportunities, reviewing and applying for scholarships, applying for financial aid, making college decisions, and preparing for the transition to postsecondary pursuits.

Dual-Credit Opportunities

Educate students about dual-credit opportunities that the district provides. Options like AP courses, Running Start, college in the high school, and CTE with articulation agreements are examples of college credit courses that will attract students in the registration process.

Recommendations Based

on Career Interests

Educate students and parents on career pathways that help students connect course selections with their career aspirations. For example, if a student is interested in a health science pathway, materials should provide clear course recommendations at each grade level to guide the student and their family through the registration process. In addition, if there are magnet schools or specialized programs within the district related to career pathways, schools should describe the process for accessing those choices along with key information about their programs.

Course Descriptions

Provide everyone with a list of all courses including a brief description of concepts taught within each class. It is critical to show courses that are part of prescribed or recommended pathways so that all students understand the necessary progression of courses. Finally, it is important to communicate key information such as which courses offer dual credit, meet NCAA requirements, and are accepted by local colleges and universities.

DESIGNING A COURSE REQUEST PROCESS

All too often in secondary schools, course request processes are impersonal and can undo significant gains made during preceding phases of strategic scheduling. In many schools, hundreds of students are brought to the theater or gymnasium to watch a presentation, and then they complete their course requests for the upcoming school year. Or counselors in ratios of hundreds of students to one counselor move through English courses and have all students request their courses. In these cases, students are not receiving individualized assistance and encouragement to sign up for stretch courses to improve their postsecondary readiness. This is not the fault of counselors, it is a result of imperfect systems. Schools must pay attention to the mechanics of its course request process so that it furthers CCR goals, and this intentional process must be designed far in advance of when students actually submit their course requests.

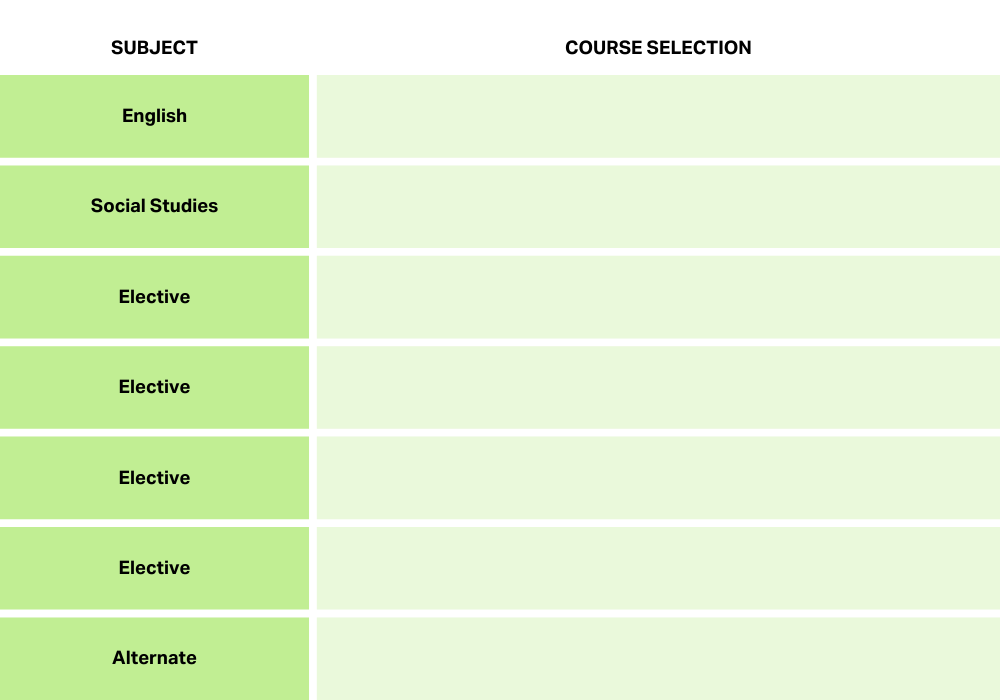

Table #8 is a sample of the types of course request forms frequently used. Juniors and seniors are presented with subjects that they must complete to receive a high school diploma and then are left with a range of elective choices to navigate. When this type of choice is coupled with limited counselor capacity for personalized advising, it places a premium on family background knowledge to navigate these decisions. Families with adults that previously attended higher education are much more likely to select challenging mathematics and science courses or dual-credit coursework as part of their elective offerings. And students — often from lower socioeconomic backgrounds — end up choosing the path of least resistance., completing the majority of their high school graduation requirements by taking multiple physical education courses, teaching assistant, early release, late arrival, etc., as their electives.

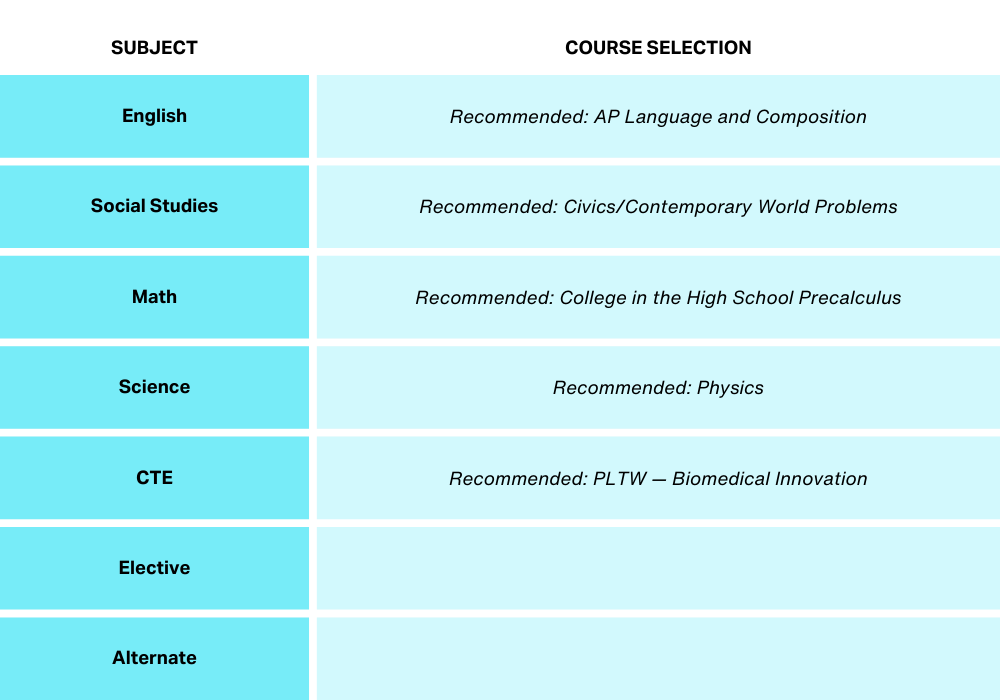

The course request form in Table #9 is incredibly different. Here, the school uses the form as part of its intrusive advising system.7American Institute for Research. “Student Advising: An Evidence-Based Practice.” Midwest Comprehensive Center and Great Lakes Comprehensive Center for the American Institute for Research, retrieved 10/1/2023 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED599037.pdf. Considering the student’s stated postsecondary plans and objectives, the recommended courses consider the student’s need to have a strong STEM background and course intensity as part of their postsecondary preparation. Is it possible to use a form like the one in Table #8 and still have equitable outcomes? Yes, but it requires a lot of individual conversation and guidance for students. And most districts and schools do not devote the time and resources for this to happen; it cannot take place with hundreds of students in a theater choosing courses nor in an English class where counselors are working with hundreds of students over the course of a few days.

Table #8: Senior Course Request Form That Can Lead to Inequitable CCR Outcomes

This is an example of a course request form that can lead to large inequities and should not be used. Course request forms like this are often geared toward high school graduation requirements where only required subjects are listed on the form and students and families are left to choose from a number of “elective” options that have large consequences for their postsecondary preparation and readiness.

Table #9: Senior Course Request Form Tailored to Individual Students and Their Postsecondary Pathways

This is an example of a student course request form for a student interested in health science careers after high school. Instead of listing four electives and requiring students to research the value of additional math and science courses for postsecondary preparation (Table #8), courses are preselected during guidance and advising. Students can opt out but must discuss with an advisor and involve family/guardians in the decision.

School districts getting the best and most equitable results have the following combination of characteristics:

- They invest heavily in advisement over multiple sessions to ensure all students have personalized attention and encouragement to sign up for intense coursework.

- They reduce the choices and options for students to make it easier to navigate the array of different pathways.

- They focus their course selection process on student postsecondary aspirations first and meeting graduation requirements as a byproduct.

- They fill in the course request form with preselected challenging coursework and have students and families opt out and/or actively recruit students into the challenging coursework to ensure all students are college and career ready.

Summary

All too often, schools dust off the course catalog and request form a few weeks before registration, make small revisions, and roll out the process to students. In these settings, students receive a 50-page catalog to read through, and they receive very little guidance on how to make these meaningful, consequential decisions. The result is student course requests that look exactly like previous years, perpetuating existing disparities.

Additionally, schools often overlook the process of actively addressing staff and student mindsets discussed in Phase 2. If students are not aspiring to take intense courses and/or staff do not believe that all students should be accessing intense coursework, then schools will have tremendous difficulty making inroads and changes in course-taking patterns and CCR outcomes. It is imperative for schools to devote adequate time to confront these issues head on and develop robust and effective tools to ensure all students and families have access to the necessary information to guide their decision-making.

Up Next

Phase 4: Collecting and Analyzing Course Requests

Course requests play a pivotal role in the strategic scheduling process, providing a foundation on which to align district and school objectives with students’ aspirations. They go beyond class selection, acting as a strategic tool to create a holistic and adaptable learning environment that supports student growth and prepares them for success in college and career.